2013

RYCA hits REFRESH

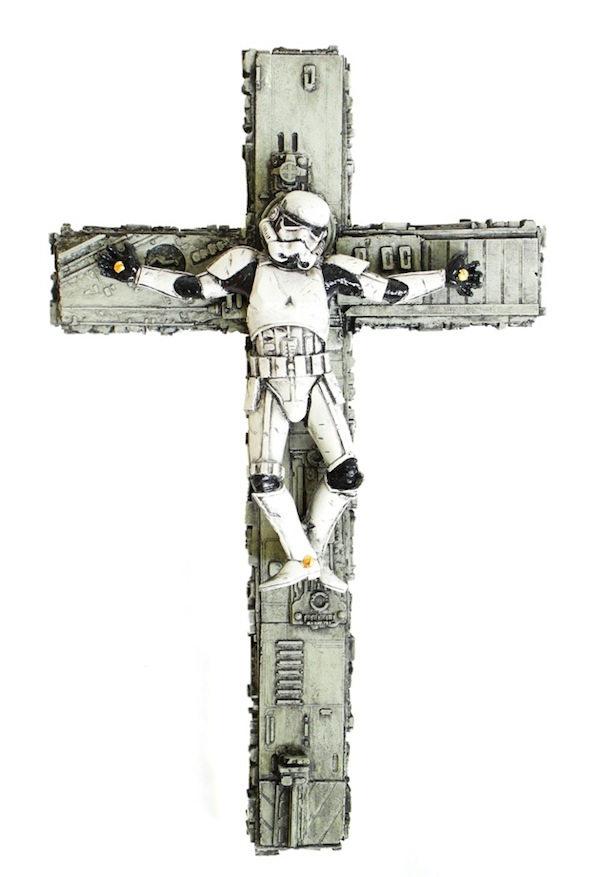

For East London artist RYCA, you could say all the world is his toy chest. Drawing inspiration from Pop Art and London’s street and stencil art movement, he’s managed to create a playful, light-hearted world revolving around a few of his favorite things, comic books, sci-fi movies and most importantly, Star Wars. Embracing the Digital Age’s devaluation of original works due to the easily reproduced and proliferated nature of imagery on the Internet, RYCA’s work riffs on iconic pop culture images, often combining two recognizable subjects in a single work to create what he calls “visual jokes.”

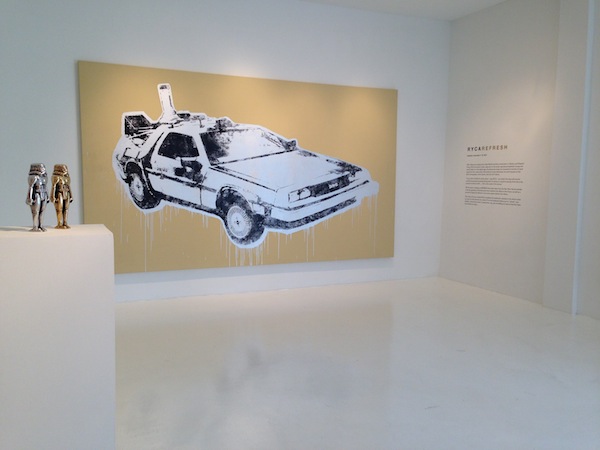

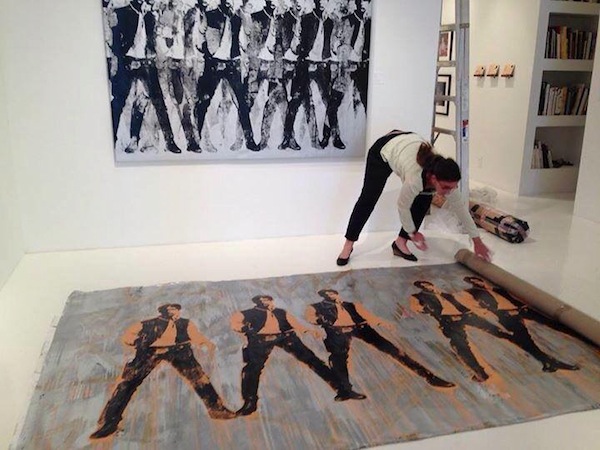

His solo exhibition REFRESH–a pun on the keyboard’s F5 key, which refreshes your web browser–borrows classic Andy Warhol imagery and “refreshes” them with subjects from Star Wars and other movies, such as Back to the Future, Aliens, and Ghostbusters. The show opens this Saturday night November 9 at Wynwood’s Robert Fontaine Gallery and runs through November 23. I caught up with RYCA as he was preparing for the show to talk pop culture, the Internet and, of course, Star Wars.

WC: What is it about pop culture icons that inspires you to create?

RYCA: I think it was sort of looking at the ethos of my favorite artists, like Andy Warhol and Roy Lichtenstien, and the way they approach their art, and that sort of thing inspired me. When I was at school learning about art and stuff, the Internet came in, and you had this resource to a generation of artists. There hadn’t been any artists who had had that kind of tool at their disposal. For me, at a young age, using the Internet and reading about those guys and what they do, the two sort of went hand in hand. In a way, it was like images, videos, information became not only easier to obtain, but even less valuable to me.

Warhol was famous for saying, what’s the point of reading books when you can just look at pictures. The Internet is there, and it’s worse now because you can send stuff, and if you subscribe to blogs, you’re not even looking for pictures, you’re just given them. It’s even easier. And it’s just that, it’s like what keeps reoccurring, what was the stuff I was looking for when I was at school. And it was around the time that the Star Wars films had been re-CGIed and re-released in the UK in 1996, and it all coincided. And I got into toy collecting and the Internet was like this thing, and you could go on eBay and find stuff, you didn’t have to go hunting. It was all a weird thing. It was all new. And it was just like every day you could look at this stuff. It wasn’t like you had to buy books. It didn’t cost you money to research. And its’ that thing spilling over into my work, and I remember my final years at school, all my coursework was Star Wars-related, and I’m still doing that now.

What is it about Star Wars, in particular, that you find so compelling?

The whole thing is like a fairytale and I went to a mixed faith school in East London, so it wasn’t solely learning about Christianity, and it wasn’t a Catholic school. In fact, the majority of my friends at that school were Muslim, and we had everyone of all faiths. It was very mixed. On the curriculum, we were made to learn about everything. It was good, in a way, because you’re not leaving school ignorant to what’s around you. I’m not of a faith background, and it was like Star Wars was like this story, and I just saw it all as crossing over. For me, it was like, well, Star Wars could be a valid religion, give it 1,000 years. Who’s to say it didn’t happen? So I adopted it then as, yeah, I’m going to find out about all of this stuff, all right. It’s people’s imaginations. For me, it remains now, if it’s not stronger, it’s like there’s parts to the story that sort of crossover and if it was written in a different context, it could be a Bible. You could extract it from the Bible. And it’s just nuts.

You mentioned earlier that you’re interested in the devaluation of images, as they were being reproduced and proliferated first by Warhol, and now through the Internet. What about that do you find interesting?

It brings up questions about ownership, and in a naïve way, I don’t really know who or what is owned. There’s clearly some stuff that you shouldn’t do and you can’t do, but then there’s massive grey areas. It can go back to Warhol and Lichtenstein, if you look at their work, and the way they approached their work. It was kind of like they were giving you the thumbs up or the greenlight to kind of do whatever you want, as long as you put it in an artistic context. It’s not straight bootlegging. If I was to pump out Star Wars t-shirts that were just the film posters, I’m going to get in trouble, but I try to mix it in with the stuff that I like, so obviously the Banksy street art movement. I remember getting into it in the early 2000s. I had started college, and in London it was massive, but it was very underground.

I found an old folder recently of propaganda stuff because we had a project where we had to create a world leader as an action figure. I did Stalin, so that led me down the propaganda Russian road. I found this old computer and inside that research folder was loads of Shepard Fairey work, but I was unaware it was Shepard Fairey at the time because I had just looked up propaganda. It’s really weird. That stuff has been sitting in my computer 10 years, and now I know a lot about him.

What are some of the other pop culture or historical iconography you work with, and why?

I think the point is the street art thing. I see it as a formula. And what Banksy did, he made visual equations that were jokes with political or pop references, so I just saw this stuff—a lot of it was happening. Shep was doing the same thing. There were a lot of artists in London doing that stuff, and I thought, I’ve got ideas that fit this formula. It wasn’t trying to mimic anything. It was just like, oh, I think I can do my own stuff. At the same time I was a student, and I didn’t have much money to buy art, so it was like, well if I make my own, it’s not any cheaper, but I think I can do something, so the Star Wars stuff and just messing around, like the Mona Lisa. It was inspired by Banksy’s mocking of the Mona Lisa. It was taking it another step further. Just looking at stuff that existed, and that carries over into my new work, which is an homage to Warhol and other pop artists, and then twisting them. If you think of Warhol’s whole ethos, you think, if he was still around, would he be pissed at people doing what I’m doing or would he actually think this is the product of what I did? This is the result of his actions.

Tell me about your work in the street art movement.

I was never a prolific street artist. For me, it was about street art as a formula. Street art, someone else branded it street art. Most guys who do street art don’t call it street art, they just consider it art in public space, so I’ve done stuff, quite big walls and bits and pieces. But it wasn’t really important to me because my stuff wasn’t politically driven like Bansky’s commenting on government. My stuff’s really not heavily focused in on the powers that be, it’s more focused in on the stuff that I like. It’s nothing more than these worlds colliding, but it’s just movies and comic books, and stuff that interests me.

I just thought it never needed to go on the street because it didn’t have that message. The stuff that Banksy’s done, it works on the street, and not everything needs to. I think that’s a big problem with street art today, you think, oh I’ve got to get up and put this stencil on the street. And if they don’t, it’s not valid. It’s kind of like, stop wasting your time and just do it if it’s really worth doing. If it’s a comment on Syria right now, then do that. Don’t do Ronald McDonald holding a US flag again, please don’t do that.

Tell me about the sign-making and word art side of your work.

I’ve been making art for seven years. When I first started, I was making prints and some signage, and stuff creeping over. It’s the same sort of formula, taking the aesthetics of British pub signs, and reworking them with rap lyrics or movie quotes, so it’s like pop art. It’s the same formula, but just different looks. Over the last two to three years, I’ve divided my worlds and split it down the middle. It’s almost like I’m a schizophrenic divide. So there’s the RYCA stuff, which is movies, pop art, Warhol, street art-looking, stencil stuff, easily classified. And now, the Ryan [Callanan], the stuff under my real name, is all the signage work. The feedback I was getting in the UK was keep that under your real name. It’s got more potential to be taken seriously as something, so you should disconnect them. I’ve been doing that the last three years, and it’s been working. They’re two entities, but I’ve done the shows as same person at the same time. If I come up with an idea and think that’s pretty cool, I can put it on Box A or Box B, and sometimes I even cross-reference myself. It’s really weird.

Tell me about your new show REFRESH.

REFRESH is a pun, so F5 on the keyboard is refresh your website, especially if you’re a person who’s looking on ebay and you’re trying to bid the last minute, you hit the refresh button. The other meaning is taking classic Warhol imagery and changing the subject to Star Wars or movie-related stuff. Generally, it’s kind of Star Wars heavy, but I’m trying to introduce other iconic films that stand out in my mind. I’m not really trying to tune into what I think might be popular. I think what I’ve done all the time is to just do what I like, and there’s always people going, yeah, alright, you’ve tapped into my brain and filled the gap on my wall with exactly what I wanted, which is quite humorous. Other times, it’s more of a celebration of something iconic from a film, and that’s all it needs to be, or a cross-reference. Light-hearted and humorous, I guess that’s my formula.

REFRESH opens Saturday November 9 at 5 p.m. and runs through November 23 at Robert Fontaine Gallery, 2349 NW 2nd Ave., Miami, FL 305-397-8530.