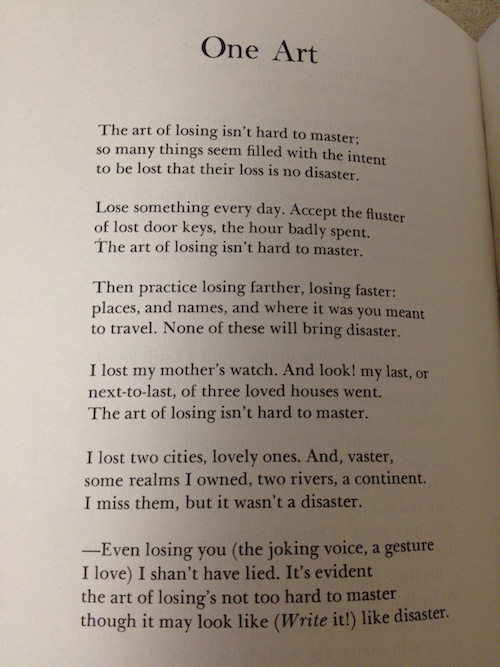

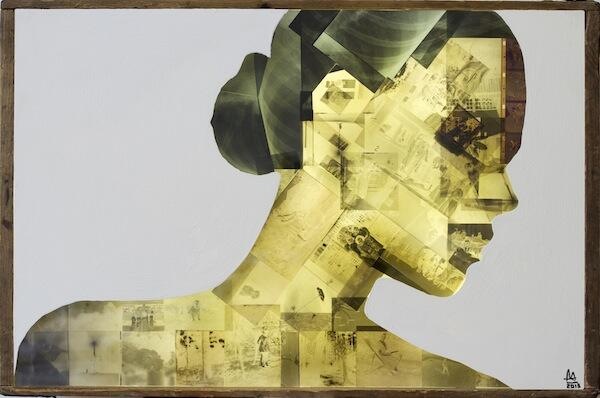

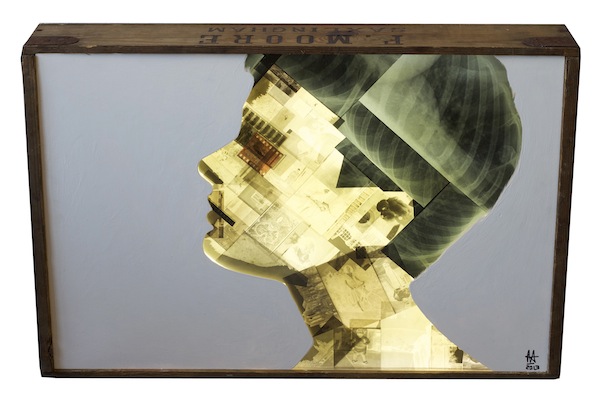

OPUS, 2013

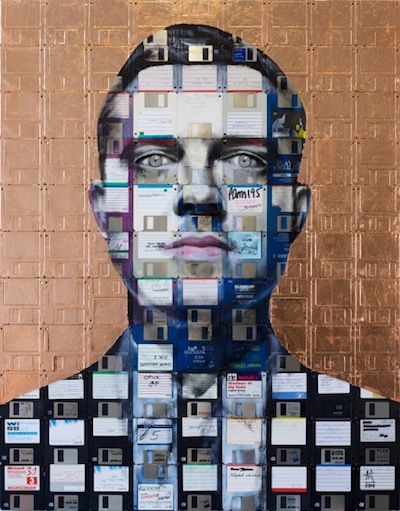

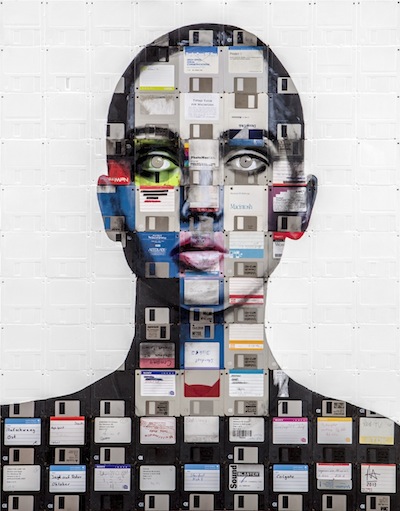

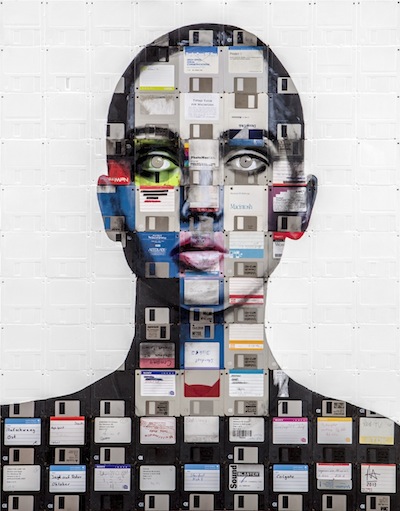

Studying one of Nick Gentry’s portraits, a pair of steely eyes look back at you with a stoic, unsmiling, sometimes stunned, expression. The face is decidedly beautiful–almost too beautiful–with perfect proportions and symmetry, hair smooth and sleek, often slicked away from the face to further show off large, luscious lips, an attractive jawline, a delicate collarbone. The London-based artist paints these large scale portraits onto a canvas of used floppy disks. His newest works are light box portraits composed of x-rays and film negatives layered in collage. So what exactly are we looking at? And is it human?

I sat down with Nick while he was preparing for his solo exhibition XCHANGE at the Robert Fontaine Gallery in Miami’s Wynwood Arts District, on display now through May 4. Here’s what he had to say about his artistic process, technology, and the rise of social media in relation to identity, privacy, and security.

WC: How do you gather the materials and how do they manifest in your work?

NG: People contact me and contribute the materials. That’s the starting point, and, to me, it’s the most important part. It’s a social art project. It’s quite inspiring to get into my studio and find a box of disks or x-rays or film negatives from people from different countries. It’s the starting point, but it’s also the end point because people come to the shows and they see their things in the artwork. It’s like a circle.

I began working in this medium about four years ago. I wanted to build substance into the actual canvas. I thought, why not create something with the canvas? Now, I’ve actually made the canvas the subject. It’s like a reversal of traditional portraiture in that the canvas is the subject and the actual image on top is just a gateway to it, an access point. It’s a flip. People ask me, “Who is this person?” Really, it’s the other way around. You can look at the face and say that’s the subject, but it’s the materials. It’s an imagined identity. I wouldn’t even say it’s necessarily a human. It’s just an imagined identity that’s created from the assemblage of those parts.

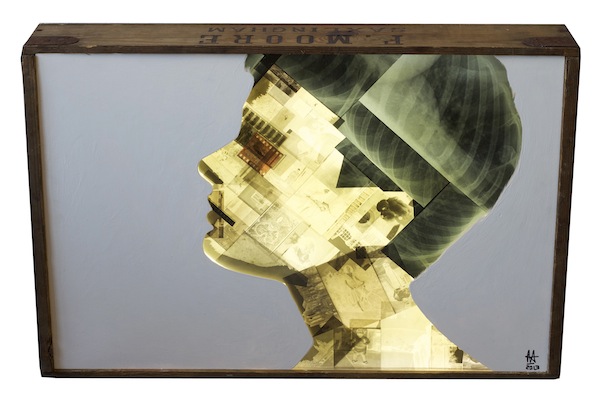

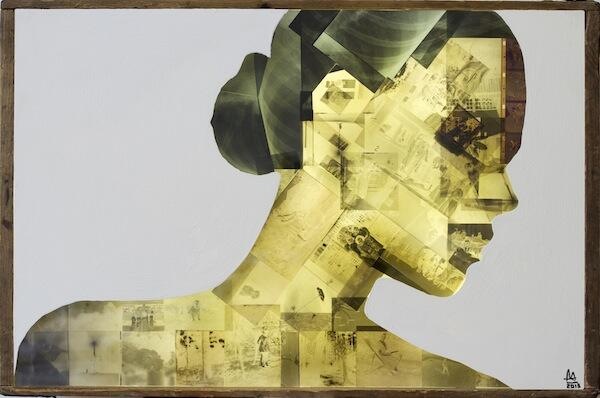

When you think back, you have all these memories and all of these things that make up you, as a person—your identity. It’s a history of the things that happened in a life collected into one portrait. With my new pieces, I’m using things like x-rays, which is an emotional history, as well as a biological history, so it’s a whole cross-section of an identity.

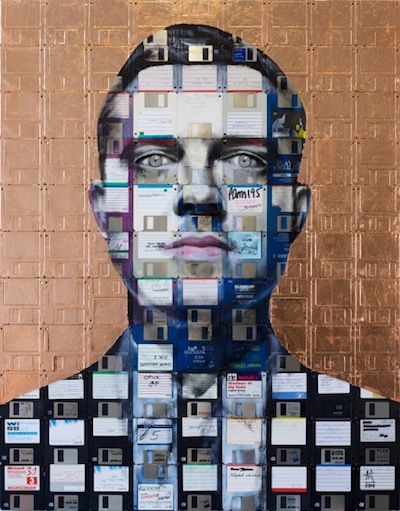

PROTOLIFE, 2013

Your portraits are composed of used technology from a number of different people. Are they meant to create a composite identity?

It’s communal and I love that part of it because I think we’re all connected—it seems that we all are. To me, what I’m doing is creating a person that’s a composite of a lot of different people’s histories. It’s kind of like a family tree where you can merge lots of things together.

Gentry at work on AMERICAN HERITAGE, 2013

How do you work with the materials in the construction of the art?

With the floppy disk portraits, the process starts with getting the disks down onto a piece of wood. You have to get the disks in the right positions according to tone. There are all of these different tones, highlights, and shadows in the face, and obviously the eyes, so you plot those out and position everything. Then, it’s masking off the edges to create negative space surrounding the person, so you’ve got a silhouette shape. Really, I try to let the disks show through as much as possible. One of the most interesting things with the disks is all the labels and the things that are written on them. I try and preserve that by doing the least amount of painting that I can. I’m just painting the features around the eyes, the nose, and the mouth.

At work on a light box collage in his studio at Wynwood Lofts.

I’m also working on a new series now with film negatives and x-rays, and that’s a slightly different process. I’m using old crates from the 1930s that I’ve turned into light boxes using LED strips inside. It’s a really old box, but it’s glowing, so it’s an old and new thing. I create a lid made from acrylic sheets, like Plexiglas, and I work with about five layers. In between each sheet, there’s a selection of film negatives and x-rays, and it’s like a collage. When the light is on, you get the image through the x-rays and the negatives. It’s like painting with light. I’m using it as a tonal device, creating light and shadow.

METAMORPH, 2013

What can we look forward to seeing at XCHANGE?

There’s a new series of floppy disk paintings and the new x-ray and film negative pieces. It’s about how we’re regarding ourselves in terms of privacy and how we’re living now. I’m really interested in the idea of identity, and that extends itself into the online world now because we’ve cultivated these digital identities. I think these identities we’re creating online will actually outlive us as records of our lives. It’s as simple as Facebook, but as we move forward, I think it’s going to get more sophisticated and kind of freaky. We have these actual lives and then we have records of our lives as digital identities. I wanted to make a comment on that, and the idea of privacy, protection, and security. It takes so much time to cultivate this second identity and it’s an important place. If you don’t take part, then everyone else is going to leave you behind. It’s an interesting direction that I wanted to highlight in my work. There’s a few different things I’ll install in the gallery, as well, little surprise elements based around that.

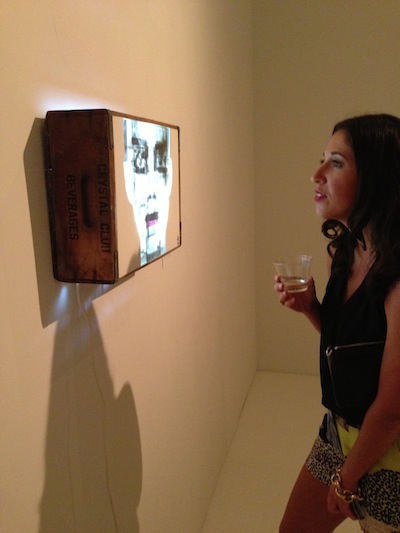

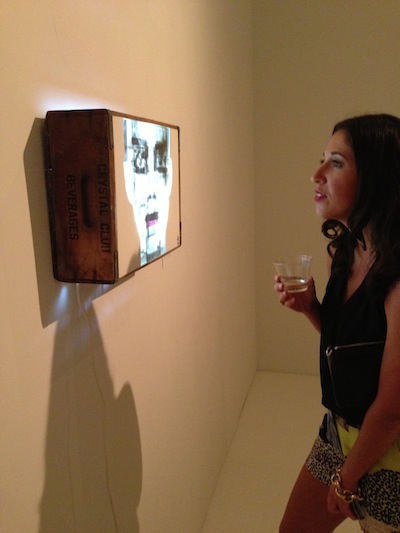

Wanderlust Chameleon studying CONTACT, 2013 on XCHANGE’s Opening Night.

Do you think privacy was more highly regarded in the age of floppy disks and film negatives?

That was the tipping point of those changes. I think of myself, and I comment on my life and where I am. It’s the artist’s job to make a comment on the present day and the moment. The floppy disk is something that really stands for that change when we started to record our lives digitally. You look at some of these disks, and the labels written on there, it’s like the first status updates. They’re the first documents out there that people were sharing. It’s private stuff, but they’re still sharing it, so it’s kind of like we were just delving into that digital life. It wasn’t so long ago, but it’s brought massive change in our lives now.

Technology seems to only be moving faster. Do you see yourself using CDs, memory chips, or other media in the future?

That’s the other interesting thing. It’s speeding up and getting faster and faster. How do we keep up? It’s crazy. I’ve used CDs in my work a few times. I find they work quite well for the eyes on a bigger scale. I do these portraits really big now. They function like an iris with the spectrum of colors. They work aesthetically, but also with the concept.

Tell us more about the eyes in your work.

The eyes, to me, are fascinating and they have been for a lot of artists through history. It’s always been the focus of portraiture. What I wanted to do was flip that and say, what if they’re made of metal? It creates a new emotion. It flips everything. The human part—all the painting and the curves and everything to make that face look so human—is juxtaposed against those cold, hard, metal eyes. When you look at them, they really change in the light because the light reflects off the surface. It changes the emotion of the face so much. It depends on where you place the portrait because of that.

I like the idea of creating this thing that’s human, but maybe it isn’t. I think of things like the film Blade Runner and androids, where we create these forms in our own image. What’s human? What’s not human? I think it’s really interesting looking into the future like that.

STARDUST, 2013

You tend to work with cool colors and unsmiling faces. Is there a mood you’re trying to evoke?

I want the maximum focus on the disks. I can’t create anything that’s overly posed. I can’t do too much with characteristics of the face. I like those restrictions, so by placing such a sterile look on the face, you just get that flicker from the eyes. The absolute focus is on the eyes and the discs.

I don’t think I could do it if I had a celebrity subject because it would be too distracting from the actual concept. I have actually painted portraiture like that before. In that case, I have to make it factually correct, so I have to choose disks and things that actually relate to that person’s life. It can be a challenge because I have to sort through a hell of a lot of disks to find something related to that person’s life and what they’re known for. I recently did a portrait for Sir Ian McKellen. I just paint for the love of it and whatever else happens is a fun surprise.

Do you work with a model or image? Or does the portrait come from your imagination and the discs?

I paint from imagination, but I tend to use references and images and combine them to find the right kind of look as a guide. I like to think of them all as just created.

ANALOGUE DAYDREAM, 2013

You’ve been in Miami for a couple of months during the show. How do you like Miami?

I love it. To me, it’s really refreshing because in London we’ve got history, and you can get bogged down in it sometimes, especially with art. In Miami, it just feels fresh. There’s an excitement about contemporary art because the focus is on it. It’s a really nice place to be. Art is definitely happening in Miami. It’s been over 10 years since Art Basel, and it’s built up into something that’s really international and well respected. I think it’s just the start, too. Miami’s got a way to go. It’s great. It’s exciting and people are really enthusiastic about art.

What do you like to do while you’re here? Will the change of scenery impact your work?

I really like the outdoorsy thing. I like being active, so it’s just a case of getting out and enjoying the weather. I like Wynwood. It’s really nice. I think a change of setting always inspires different things. I don’t know exactly how it will affect the work, but it relates to mood and how you feel. It might change the color in the work because, well, the blue sky.